Lighting The Way For Historic Preservation

| |

Attorney Casey Jordan realizes it might seem a little strange. She’s seen the looks on people’s faces and heard the questions about her willingness to take on even the most difficult projects. But when it comes to restoring and preserving dilapidated lighthouses, she said, “It’s a passion. You either get it or you don’t.”

Jordan certainly gets it, and for the past two years, she has been dedicated to obtaining and refurbishing lighthouses in Maine and Connecticut through the nonprofit organization that she created, Beacon Preservation Inc. in Ansonia.

Lighthouse preservation has become a serious avocation for Jordan, who teaches criminology at Western Connecticut State University and maintains a part-time law practice focused primarily on mediation.

Her latest project is the Penfield Reef Lighthouse in Fairfield, which the National Park Service deeded to her group in December. Currently, there’s a dispute with the federal government over who owns the underwater land on which the lighthouse stands, and that has kept Jordan busy as general counsel for the organization.

Once the dispute is resolved, Jordan envisions restoring the lighthouse to its original condition and turning it into an education center where students and the public can learn about the Long Island Sound and local ecosystems.

The government also is considering Jordan’s application to obtain the Saybrook Breakwater Light, which is the lighthouse featured on Connecticut license plates. She plans to install web cams in that lighthouse that can be accessed by visitors to the Connecticut River Museum in Essex.

Private groups are eligible to acquire lighthouses that are unwanted by the government through the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act, enacted in 2000. Those groups are required to make the lighthouse available for education, recreation, cultural or historic preservation purposes. Twelve lighthouses, including Saybrook Breakwater, were available from the government in 2008 and were located on the East Coast or in the Great Lakes region.

‘Fun And Romantic’

Back in 2006, Jordan and her husband, Dr. George Northrop, heard about an operational lighthouse in Maine that was on the auction block, and they traveled to Maine to visit the Goose Rocks lighthouse, which was built in 1890.

On a lark, the couple decided to place a bid for the lighthouse, and the government sold it to them for $27,000. “It wasn’t just about buying a lighthouse,” Jordan said. “We really believed in the preservation. It’s fun and romantic, but there’s also a finite number of these lighthouses” that are left standing.

So Jordan took leave from her teaching position at WestConn and the couple moved to Maine for nine months. Northrop became a physician in a nearby lobstering town of 350 people. The couple also established their nonprofit lighthouse preservation organization and convinced paint and home supply companies to donate materials for the project.

Restoration involved scraping paint off of iron and laying new floors that looked true to the original flooring, which had mostly rotted away.

Jordan said the biggest challenge involved logistics because the lighthouse is accessible only by boat. “Are you ready to hoist up a generator and compressor out of an inflatable boat? Because that’s what you have to do,” Jordan said. As the work progressed toward the final touches and furnishings, other questions emerged, such as: “What happens if the antique armoire falls into the water?” Jordan said.

Jordan, her husband and two family members essentially did all of the work, and the Maine lighthouse is awaiting the solar and wind energy equipment that will provide power. There’s also a desalinization system to convert salt water into drinking water and a composting toilet.

In all such lighthouse transactions with the government, the Coast Guard retains the right to maintain the light and fog horn.

Beacon Preservation offers up overnight stays at Goose Rocks to people who support the group’s cause, and those funds will be used to refurbish other lighthouses in the future, Jordan said.

Roll On Paint

For Jordan, lighthouse preservation isn’t a wild leap. She has been interested in restoring historic structures since she bought a 23-room Victorian house in Fort Edward, N.Y., in 1988. Along with two historic lighthouses, she owns several refurbished historic homes, though she plans to sell the Fort Edward property to help fund her lighthouse initiative.

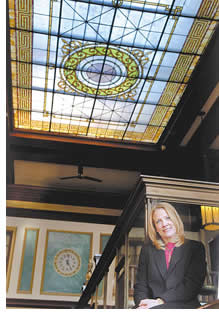

So why a lighthouse preservation group in inland Ansonia? The building where Jordan operates the non-profit group and her part-time law practice is an 1865 Greek Neoclassical building that once housed the Savings Bank of Ansonia; she and Northrop restored it a few years ago.

But for Jordan, who grew up in Tulsa, Okla., a lighthouse on the ocean appeals to her appreciation for architecture and nature in a way that an historic house cannot, and she has been contacted by numerous volunteers who are equally interested in her group’s cause.

“Some people want to roll on paint and see the immediate results of their time, and historic preservation allows them to do that,” Jordan said.

And there’s no better feeling at the end of a long day of work than firing up the grill and watching the sunset from the deck of a lighthouse that will provide guidance and protection during the night, Jordan noted.

“You’re not just saving a lighthouse,” she said, “you’re saving what it stands for.”•